TABLE OF CONTENTS

The complicated story of parking was written by UCLA Professor Donald Shoup in 2005. His groundbreaking work, The High Cost of Free Parking, shares the history of parking policies in the United States, outlines their negative outcomes, and urges policy changes to align our relationship to parking with our values of equity and sustainability.

While the Parking Reform Network (PRN) highly recommends Dr. Shoup’s book, we understand that not everyone has the time to read all 800 pages of it. To help educate people on the state of parking in American cities and how parking policy could work for equity and sustainability instead of against them, Parkade founder Evan Goldin wrote a summary of the book. With Professor Shoup’s permission, Evan published his summary on parkade.com in 2019, and the summary you’re reading now is an updated version of the summary — a collaborative effort between Evan and PRN.

Working his way from the history of how curb parking transitioned from handling horses to handling cars, all the way to mandated parking requirements for new and existing buildings of all kinds, Dr. Shoup shows how our relationship with parking negatively impacts air quality, congestion levels, construction costs, municipal and business revenue, the sense of community in our neighborhoods, and even the cost of goods.

Thankfully, Dr. Shoup proposes solutions. In fact, he and 45 other academics and practicing planners affirmed them in his 2018 book, Parking and the City. By removing mandatory off-street parking minimums, charging fair market prices for curb parking, and creating parking benefit districts that receive the meter revenues from their streets to invest in public services, we can make significant progress toward solving America’s parking problem. And that can help improve the quality of life in our cities, protect our natural resources, and promote social justice.

This summary is divided into two primary sections. The first (A Quick Tour of Shoup’s Text) is a brief summary of the major themes and ideas presented throughout The High Cost of Free Parking. The second section (The High Cost of Free Parking, Bite-Sized) is more thorough, taking a “bite-sized” approach to the major details Dr. Shoup fleshes out in his book. Basically, if you’re really pressed for time, reading the first section will give you the big idea. If you have more time (an hour or so), read both sections.

Whether you read just a few sections of this summary or the entire thing, it’s important to keep in mind that The High Cost of Free Parking was published in 2005. Many of its statistics are a little dated at this point, but they’re still useful and will give you a solid understanding of the parking situation on the ground (or below it, or above it).

We hope you enjoy this Cheat Sheet to The High Cost of Free Parking and find it useful.

Typical American commercial office complex, with most land to parking (via Google Maps).

Americans, rather than trying to manage a common good with prices, have tried to legislate a vast abundance of parking without much thought for the consequences. And the consequences are dire.

Almost every municipality in the United States has enacted “parking minimums” over the last century, putting in place government rules that mandate specific minimum amounts of parking in new or changing buildings. These minimums have produced poorly designed cities, where more land is often devoted to parking than to the primary purpose of the buildings on the site. Off-street parking requirements reduce density because each building has its own parking that’s typically unavailable to the general public.

Minimums have eviscerated the ability for most places to install parking meters, because meters can’t compete with free parking.

Parking minimums have broken the link between using parking and paying for parking. With 99% of all parking in America free, most people drive to where they are going (87% in 2005, for example). Meanwhile, prices of all goods — especially housing — have gone up to indirectly cover the cost of providing those parking spots. With very rare exceptions, those costs are paid by cyclists and pedestrians at the same rate as drivers, even though they don’t use parking.

Of course, it isn’t that everyone wants to drive. Parking requirements have helped create the illusion that almost everyone prefers to drive everywhere alone. But the reality is that everyone prefers the best value, and parking requirements keep the cost of driving so low that solo driving is the cheapest form of travel. If all drivers had to pay for their own parking, fewer people would “prefer” to drive everywhere.

With the number of car trips bolstered by parking minimums, the world has become much more congested and polluted. When people arrive at their destination and find free, open parking spots, it’s not because the market is setting the price of parking. Free parking ensures nearly all parking is consumed, so drivers spend far too much time cruising for their spot.

Citizens generally don’t want to pay more for parking because the money feels like it just disappears and doesn’t benefit the person paying. To solve this problem, communities should charge for parking as part of a “parking benefit district,” where some or all of the money fed into the meters would go directly to the community where the meter resides.

Doing this would create a way for locals to charge for parking, harnessing the ownership so many people already feel over the curb at their home or business to actually become beneficiaries. Parking benefit districts would also create the necessary political support to charge market prices for curb parking.

There will be many counterarguments, of course. “This is unfair to everyone” or “This is unfair to poor people” will likely be the main ones. To counter that attack, remember that low-income residents are far less likely to own cars, meaning today’s policies actually have poorer residents subsidizing wealthier drivers.

Ability to pay is just one of many factors — such as number of car occupants, value of time savings, or parking duration — that influence a driver’s choice of where to park. Directly charging drivers for their parking is much fairer than forcing everyone to pay for it indirectly.

When it comes to parking policy, America has become a strange place. In the country that proved capitalism the winning governance model, we let planners tell us exactly how much parking is needed at every type of residence or business, and we take it as gospel.

A world with market-dictated parking would allow consumers a choice — pay more for your goods and have easy parking, or pay less for your goods and pay the meter (or walk, bike, or take transit).

There are a few other ways to move toward smarter parking policies: unbundling parking from rent/condo deeds, deciding parking and building approvals separately, and — if minimums are still a factor — having minimums that focus on car-parked hours rather than the raw number of spots (to encourage better usage). These would all help tremendously.

Fixing the status quo won’t be an easy fight. But until we do, if motorists don’t pay for parking, society at large must pay for it in other ways — traffic congestion, energy consumption, degraded design, urban sprawl, and the high opportunity costs for land.

One of the highlights of Shoup's writing is his ability to craft metaphors that bring these concepts to life. Here are some favorites from The High Cost of Free Parking.

Road construction

Suppose cities financed roads the same way they finance parking. Instead of paying for roads through gas taxes, vehicle license fees, and general funds, governments could require new buildings to pay for adding enough road capacity to handle all the additional vehicle trips generated. For example, each new building would pay for street widening and intersection flaring to meet the added demand for driving, so that traffic congestion wouldn’t increase. Like the cost of parking, the cost of roads would be shifted from drivers to higher prices for everything except driving. Would this be a good idea? No, because everyone but drivers would pay for roads, and the cost of new buildings would explode to shoulder road construction costs.

Minimum telephony requirements

Imagine what would happen if urban planners arranged to have the charges reversed for all telephone calls, so the called parties, not the callers, pay for telephone calls. Let’s further imagine that the cost of all the reversed charges is bundled into every property’s mortgage or rent payment without separate itemization, so that nobody seems to pay for using the phone. Because all the calls are free to the callers, the demand for telephone use soars. To avoid chronic busy signals, cities set minimum telephone requirements so that each new building provides at least enough telephone lines to handle the peak number of calls. Soon everyone expects every building to have at least one telephone line for each occupant plus additional lines for fax machines, computer modems, and burglar alarms. Developers pass the cost of providing this telephone capacity on to the occupants, raising the price of all goods and services, including housing.

Rent control for cars

Free curb parking is like rent control for cars. High demand for a limited supply of free curb spaces predictably leads to shortages. To deal with this problem, cities impose off-street parking requirements that increase the cost of housing. Free parking for cars thus raises the cost of housing for people.

Why isn't gasoline free?

Gasoline is a basic necessity for cars, but this doesn’t mean gasoline should be free. Filling stations offer different grades of gasoline (with both self-service and full-service) at different prices, and this is fair. Parking spaces differ from one another chiefly in location, and different prices in different locations are likewise fair.

Minimum dessert requirements

If cities required restaurants to offer a free dessert with each dinner, the price of every dinner would soon increase to include the cost of a dessert.

To ensure that restaurants didn’t skimp on the size of the required desserts, cities would have to set precise “minimum calorie requirements.” Some diners would pay for desserts they didn’t eat, and others would eat sugary desserts they wouldn’t have ordered had they paid for them separately. The consequences would undoubtedly include an epidemic of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. A few food-conscious cities like New York and San Francisco might prohibit free desserts, but most cities would continue to require them. Many people would get angry at even the thought of paying for desserts they had eaten free for so long.

Gained weight? Here’s a new, free wardrobe.

Off-street parking requirements eliminate any incentive to charge for parking in proportion to a car’s size. When cars grow larger, cities typically respond by increasing the minimum width and length of the required parking spaces so that drivers can safely and comfortably open the doors of their bigger cars without marring the finish of adjacent vehicles in parking lots. Imagine the public health problems if people were always given an entirely new, free wardrobe of larger clothing whenever they gained weight.

Minimum lunch requirements

People need food to live, but this doesn’t mean planners should require every office building to provide a lunchroom big enough to supply a free lunch at noon for everyone who works in that building. If all restaurants in the city were free, cities would soon need to impose lunchroom requirements for all office buildings, so that office workers wouldn’t overwhelm the nearby free restaurants. To satisfy the peak demand for free food, these lunchroom requirements would probably look exactly like off-street parking requirements.

The price of gold

Suppose cities had always charged market prices for curb parking and had let private decisions determine the quantity of off-street parking. Parking wouldn’t be free, but few people would complain about a shortage of it. Gold is scarce and expensive, for example, and is essential for many purposes, but there’s no shortage of it. Shortages result from underpricing.

If you read The High Cost of Free Parking a while ago and need a high-level refresh — or if you’re more of a skimmer than a reader — this section is for you. We’ve pulled out the text’s key points and organized them thematically.

Initially, drivers parked at the curb, where they had previously parked their horses. But there wasn't enough room for all the cars, so planners created parking requirements. That solved one problem and created many others. Today, restaurants typically need three times the land area of the business for parking, and commercial buildings need two times the area.

At first, a developer might pay for parking. Then the tenant pays. Then it's the customer’s turn, in the form of higher prices. The cost of parking has seeped into everything we buy.

When the cost of parking is hidden in the prices of other foods and services, no one can pay less for parking by using less of it. Bundling the cost of parking into high prices for everything else skews travel choices toward cars and away from public transit, cycling, and walking.

One of the biggest problems with off-street parking requirements is that planners calculate demand based off a $0 price for parking. Because there's so much parking, this drives the price of parking to nearly zero.

If cities didn’t require parking, the market would supply it only when profitable, like the sale of gasoline. There would be fewer spaces, and spots that were frequently empty would be redeveloped.

Most planners and elected officials don’t recognize that parking requirements encourage more driving.

Studies show no evidence between parking restraint (elimination of parking minimums) and economic visiting.

Mobility and proximity are two ways to improve accessibility. The problem with using off-street parking requirements to provide mobility is that they reduce proximity. Induced demand further reduces mobility by increasing congestion.

American cities put a floor under the parking supply to satisfy the peak demand for free parking, and then cap development density to limit vehicle trips. European cities, in contrast, often cap the number of parking spaces to avoid congesting the roads and combine this strategy with a floor on the allowed development density to encourage walking, cycling, and public transport.

All potential drivers can park free even at the time of peak demand — a policy we can call parking satiation. Everyone can park free everywhere because parking requirements keep the parking supply high enough and zoning keeps the human density low enough.

Because curb cuts aren’t available for on-street parking, and because off-street spaces are often unused during weekdays when residents are at work, off-street parking spaces effectively reduce the available parking supply.

The economics of shared parking help to explain the appeal of a successful downtown. Everybody wants to park once and walk around to shop, dine, and see a show. A dense downtown can provide this experience, but off-street parking requirements reduce density because each building has its own parking that’s off-limits to the public.

Because motorists pay for parking indirectly, the cost of parking rarely deters anyone from owning or driving a car. The result is increased automobile dominance, traffic congestion, air pollution, and urban sprawl. Parking requirements help explain why America’s attempt to be urbanized and fully motorized at the same time is destroying both the benefits of cities and the advantages of the private car.

Parking requirements and free parking have helped to create the illusion that, all things considered, almost everyone prefers to drive everywhere alone. But everyone actually prefers the best value, and parking requirements keep the cost of driving so low that solo driving is the cheapest form of travel. If all drivers had to pay for their own parking, fewer people would “prefer” to drive everywhere.

Some people think cities shouldn’t charge for curb parking because it’s a public good, but curb parking is exactly the opposite of what economists define as a public good. Public goods have two economic characteristics. First, they’re nontrivial in consumption: One person’s use doesn’t reduce the amount left for everyone else. Second, public goods are nonexclusive: Once the good has been produced, charging for it is difficult because no one can be excluded from receiving its benefits.

Predictability of travel time is an important goal for a transportation system, but the time needed to find underpriced curb parking is highly unpredictable. When all curb spaces are occupied, the major determinant of search time is luck. Finding a space may take less than a minute if you pull up just as someone else is pulling out, or it may take half an hour. Drivers who want to avoid arriving late have to leave early in case it takes a long time to find a parking space. Since raising the price of curb parking reduces the variability in the time required to find a curb space, it also reduces the uncertainty of travel time — yet another benefit of right-priced parking.

Cities incentivize cruising by underpricing curb parking. Three minutes might not seem like too long to spend cruising for a curb space, but that adds up to an astonishing amount of excess driving. Charging the right price for curb parking eliminates the incentive to cruise and reduces traffic congestion, energy consumption, accidents, and air pollution.

Two major problems — one practical, the other political — prevent cities from charging the right price for curb parking. The practical problem is how to collect the revenue, and the political problem is that everyone wants to park for free.

Charging for parking is sound economic policy. Good public policy means that any public service with an easily identifiable direct beneficiary should be paid by that beneficiary, unless sound arguments in favor of an explicit subsidy can be made. But many countries seem to have adopted the opposite approach: namely that whatever subsidies exist now are right, so the onus of proof for any change lies with the proponents of change. This position isn’t logical, but it’s the one that we have to deal with.

If nonresidents pay for curb parking, and the city spends the revenue to benefit the residents, charging for curb parking can become a popular policy rather than the political third rail it often is today.

Market prices can create a few curb vacancies, increase turnover, reduce search time, and attract customers who are currently kept away by parking shortages. Parking won’t be free, but it will be more convenient.

Merchants may oppose charging for parking on the grounds that it will drive away customers, but this fear is often unfounded. Parking consultant Mary Smith explains that many customers are short-term parkers who care more about the convenience than the cost of parking. If merchants realize that convenient parking is more important to customers than free parking, and are guaranteed that their business districts will receive all the meter revenue, they’ll soon support market-rate prices for curb spaces.

Many residents think they own the parking spaces in front of their homes — or at least they act like they do. Rather than fighting this perception, cities can take advantage of it by treating residents like the landlords they think they are.

Policies that increase the cost of cars are never popular or easy to implement, with the exception of parking benefit districts. They meet all seven of the criteria Harvard University Professor Arnold Howitt deemed critical to the political administrative feasibility of policies to restrain automobile use:

Some neighborhoods may choose to retain free curb parking, off-street parking requirements, and no curb parking revenue, but right now, this is the only choice cities give neighborhoods. Cities should offer the option of parking benefit districts and let neighborhoods choose.

Free parking in front of people’s homes is an ingrained social practice. In order to generate political support, benefit districts will probably need to preserve free parking for existing residents.

If curb parking is free, most residents will say “not in my backyard” to any nearby development with fewer off-street parking spaces than the zoning requires. Parking benefit districts can create a symbiotic relationship between commercial development and its nearby neighborhood because nonresidents who park in the neighborhood will pay for the privilege.

Where curb parking is treated as common property free to anyone, everyone will object to granny flats if the new residents park on the street. But suppose that a parking benefit district charges market prices for curb parking in a neighborhood with granny flats. Everyone will have an incentive to economize on curb parking. Some residents who used to park their cars at the curb will park off-street, and others might sell an old car that isn’t worth the price of a parking permit.

Higher urban land prices aren’t a bad thing if they lead to more housing, but off-street parking requirements prevent higher densities. In contrast, parking benefit districts will allow the market to supply less parking and more housing, without generating more traffic.

Parking benefit districts won’t finance curb parking but will instead create the necessary political support to charge market prices for it.

The 20th century saw a great competition between two economic systems: central planning and market prices. Central planning is essential for some purposes, but it failed spectacularly where it governed too much of the economy. Parking is a perfect example of an economic activity where planners have usurped markets without justification. We have relied almost exclusively on the command-and-control approach to regulate parking, and we have failed spectacularly.

Cities have tried to manage parking almost entirely without prices.

The only constraints on charging market prices for curb parking are political. Public concern has shifted to problems that free parking makes worse, such as traffic congestion, energy consumption and air pollution.

Market prices show that carpoolers, short-term parkers, and those who place a high value on saving time will park close to their destinations and pay higher prices. In contrast, solo drivers, long-term parkers, and those who place a low value on saving time will park farther away to save money. This pattern of individual parking choices will minimize society’s collective cost of travel.

There is no single, sensible estimate of how far drivers are willing to walk from parking spaces to their final destination. Willingness to walk depends on the parking duration, the number of people in the car, their walking speed, and their value of time.

Because of these factors, market prices tend to allocate parking spaces efficiently. Individual choices in response to market prices minimize the travelers’ total cost of walking from their parking spaces to their final destinations.

By allowing millions of decision makers to respond individually to freely determined prices, the market allocates resources — labor, capital, and human ingenuity — in a manner that can’t be mimicked by a central planner.

When automobile use began a century ago, the parked car quickly became an even greater obstacle to the flow of traffic than moving cars. The crux of the problem was that the streets were unable to move cars and to store them. This was especially true in the central business district, which had the heaviest traffic and thus the greatest demand for parking space. Hence, downtown business interests were in a bind. If motorists couldn’t park at their destination, the central business district would lose trade. But since parked cars increase traffic congestion, it would lose trade even if they could.

The ability of a transportation vehicle to bear the charges at both ends of the run isn’t a very severe test of its utility. If a private car isn’t worth enough to its owner to justify paying $2.60 to $5.20 (in 2003 dollars) a day for its storage, it’s unreasonable for the public to provide improved street space for the purpose.

We need a new Golden Rule for the price of parking: Charge others what they would charge you.

We should treat parking spaces for a restaurant (or any other land use) in the same way we treat the restaurant itself. Planners don’t say how many restaurants a city must have. We let the market provide as many restaurants as people are willing to pay for. Similarly, planners should let developers provide as many off-street parking spaces as drivers are willing to pay for. When cities require more parking than developers are willing to provide voluntarily, the result is to subsidize the car over other travel modes.

Removing off-street parking requirements would induce a few changes:

Market prices are a sensible, bottom-up approach to planning for parking, while off-street parking requirements are a confused and costly top-down approach. Market-priced curb parking and no off-street parking requirements will steer business investment toward activities whose customers and employees require less parking. The result will be more mixed-use and infill development near existing infrastructure and less greenfield development in outlying areas.

Free curb parking and off-street parking requirements are the exact opposite of what Henry George recommended. Cities fail to collect land rent from curb parking, and they impose a heavy tax on buildings.

Both property taxes and parking requirements place a burden on buildings, but property taxes at least provide public revenue.

Many houses have two curb spaces in front, so market-price parking spaces may yield more revenue than the current property tax in some neighborhoods.

If the city keeps all curb parking revenue for the general fund, it collects almost nothing because most people oppose parking meters.

Residents tend to “vote their homes” in the sense that they consider the effect on the value of their homes when voting on municipal taxes and services.

Revenues need effective political claimants, and returning the toll revenue to cities with freeways can create these claimants.

The complaint that charging for curb parking is unfair can be made against charging for almost anything. Motorists pay for most other costs of owning and operating a car (gas, tires, repairs, insurance, and the vehicle itself), but few see this as unjust. If we pay rent for our housing, why shouldn’t we also pay rent for housing our cars?

Cities can individualize — decollectivize — the cost of parking, so that we pay less for parking if we use less.

Drivers value time savings differently from one trip to another, and market-priced parking gives travelers a trip-specific, spur-of-the-moment ability to place a high value on their time. Drivers who can’t always afford to park in the best spaces can still choose to park in them on occasions when saving time is particularly important.

Because motorists don’t pay for parking, society pays for it in other ways — traffic congestion, energy consumption, degraded design, urban sprawl, and the high opportunity costs for land. Every place we have to put a car is a place we could have put something else.

A condo association could own parking spaces as common property and lease them to the residents at a price that equates supply and demand. The rent from commonly owned parking spaces could then replace all or part of the fees residents pay to maintain their association. Parking wouldn’t be free, but those who own fewer cars would pay less. After unbundling, developers would find they could build condominiums more cheaply.

If cities stop specifying the minimum number and size of parking spaces, developers and property owners can respond to changes in the demand for different sized cars by re-striping and reconfiguring the parking spaces, and then by charging for the spaces according to their size.

Because the size differences among cars are so large, charging for parking in proportion to a car’s size is fairer than charging the same price for all cars regardless of their size. After all, no one expects to pay the same rent for a 500-square-foot apartment as for a 1,500-square-foot apartment in the same building.

Popular historic styles like courtyard housing can’t be replicated with today’s parking requirements. Planners initially intended parking requirements to serve buildings, but architects now design buildings to serve the parking requirements.

Building parking to meet minimums is a hard task. The developer must forego surface parking and provide spaces within or underneath the apartment building itself. If the area in question has a three-story limit, the only alternative is to provide underground spaces, which doubles their cost of construction.

Unbundled parking will raise ownership costs proportionally for the older and less reliable second (or third and fourth) cars in a household, which often consume more fuel and produce more pollution. When people consider the price of parking a rarely used car, it may come to be seen as an expendable luxury. As a result, unbundled parking will tend to cull the cars that contribute least to mobility and most to fuel consumption and air pollution.

Most developers and landlords bundle parking with housing because the off-street parking requirements in zoning ordinances are so high. If cities require developers to provide two spaces per apartment, landlords can’t hope to rent the required spaces at a cost recovery price.

Off-street parking requirements are intended to prevent parking spillover. If curb parking is free, and new development doesn’t provide enough off-street spaces, spillover will create a nuisance for everyone. Unbundling parking from housing will — if nothing else is done — create the spillover that parking requirements are designed to solve. To discourage spillover in residential neighborhoods, some cities prohibit overnight curb parking in order to prevent residents from using the streets as their garages. A more promising approach is to establish parking benefit districts that charge market prices for curb parking and spend the revenue to pay for public expenditures in the neighborhood.

Urban planners have no training to estimate the demand for parking, and no financial stakes in the success of a development. They don’t know more than the developers do about how many parking spaces each project needs. They may, at best, know a little about the peak demand for free parking at a few land uses, but they know nothing about the marginal cost of parking spaces at any site or how to estimate the demand for parking as a function of its price. Markets will quickly reveal the demand for parking if cities cease requiring off-street spaces.

Bundled parking hides the cost of owning and using cars, and it distorts choices toward cars and sprawl. The bloated parking supply required to satisfy the demand for free parking degrades urban design and drains life from the city streets. By contrast, unbundled parking will reveal the cost of parking, reduce the prices of everything else, and give everyone the option to save money by conserving on cars and driving.

American cities now use parking meters almost exclusively in areas that were developed before zoning required off-street parking.

Requiring “enough” parking spaces in a new development does seem sensible, so what went wrong? Two things. The first problem is that planners require at least enough parking spaces to meet the peak demand for free parking, regardless of the cost. Second, and more fundamental, the parking requirements are unnecessary.

Planners use surveys of peak parking occupancy to set minimum parking requirements everywhere. In most cases, the large supply of required parking drives the market price of most parking to zero. As a result, most surveys of parking demand are conducted at sites that offer ample free parking, and the observed demand is correspondingly high. Following this circular logic, urban planners neglect both the price and the cost of parking when they set parking requirements, and the maximum observed parking demand becomes the minimum required parking supply.

If you’re advising a mayor, imagine which policy to recommend — off-street parking requirements that induce demand for cars, discourage public transit use and walking, cause air pollution, and require urban design that’s built around free parking. Or market prices, which will create curb vacancies and restrain demand for cars, reducing energy consumption, traffic congestion, and air pollution. Curb parking would pay for public investments. The decision, surely, would be obvious.

Why can’t building a Walmart and its parking lot each be considered on its own merits? Parking is now seen as a condition for development, rather than as a part of the development itself, to be scrutinized and evaluated on its own. Although parking is the single biggest land use in cities, it has managed to always become part of something else, and from that position it dominates cities.

Who can seriously contend that minimum parking requirements and ubiquitous free parking are long-term strategies to make great places and create sustainable cities? Parking requirements help planners avoid immediate conflicts over current development, but they plant the seeds of many long-term woes.

Parking requirements have become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If planners assume everybody will go everywhere by car and cities require enough parking spaces to meet the peak demand for free parking at every land use, everything will be so dispersed that most people will have to drive wherever they want to go.

In setting parking requirements, planners often consume the number of parking spaces with the capacity to park cars in them because the capacity of a parking lot or garage to accommodate parked cars is an ambitious concept. During the hours of peak demand, valet and stack parking can increase capacity by storing cars in tandem or in the access aisles, thus substituting labor for land and capital in parking cars. Automated garages, in turn, substitute capital investment and technology for parking spaces. Requirements for a minimum number of parking spaces eliminate the option to substitute labor for land and capital in providing parked-car-hours, which is the fundamental measure of what is ultimately consumed when drivers leave their cars.

Donald Shoup, Ph.D.

Donald Shoup is a distinguished research professor in the department of urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles. He holds both a Ph.D. in economics and a B.E. in electrical engineering from Yale University. His research has focused on parking, transportation, public finance, and land economics. He first published The High Cost of Free Parking in 2005.

Shoup is a fellow of the American Institute of Certified Planners and an honorary professor at the Beijing Transportation Research Center. He has received the American Planning Association’s National Excellence Award for a Planning Pioneer and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning’s Distinguished Educator Award.

Evan Goldin

Evan Goldin is co-founder and CEO of Parkade, a parking-management system used by multi-family dwellings and offices around the globe to better manage private parking. He's also a constant advocate of "Shoupism," safer streets, and parking reform. Prior to founding Parkade, Evan was the first product manager at the rideshare company Lyft and director of product at Chariot, a micro-transit provider.

Evan published his cheat sheet for The High Cost of Free Parking in June 2019.

Parkade

Parkade was born out of the belief that the way parking is used in the United States leaves a lot of room for improvement and that living or working in dense urban areas shouldn’t inherently require terrible parking options. Parkade helps apartments, condos, and offices to streamline their parking-management tasks, easily sublease parking among tenants, increase parking revenue, give tenants a lot more flexible parking options and — most important — get by with significantly less parking than a building needs today.

Parking Reform Network

The Parking Reform Network (PRN) educates the public about the impact of parking policy on climate change, equity, housing, and traffic. In partnership with allied organizations, we accelerate the adoption of critical parking reforms through research, coalition-building, and direct advocacy.

Whether your city needs abundant affordable housing, more bike lanes, or transit improvements, parking policy and parking politics are always an obstacle. PRN is here to support activists and professionals working in any discipline or policy area impacted by car parking.

You can help make a difference in how our communities think about — and act on — parking policy. Reading this summary was a great start! To go deeper, here are a few websites, videos, and groups to check out.

.jpg)

As parking management becomes increasingly digital, security becomes critical — and we’re excited to share that we've achieved a major security milestone.

Read Story

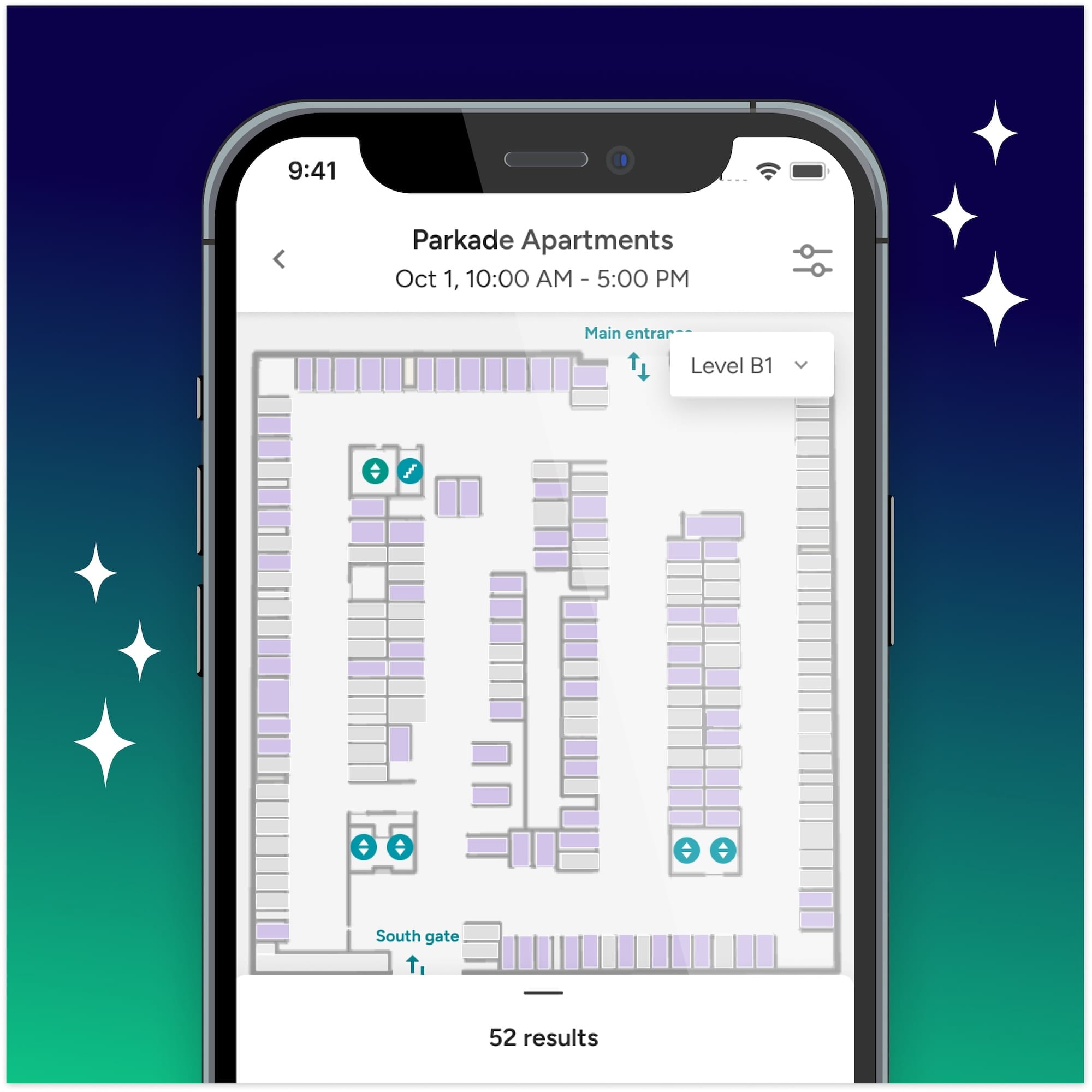

We’re thrilled to announce one of our most significant leaps forward this year: the launch of dynamic maps across our mobile and web applications.

Read Story

Now that AB 1317 is official, it’s time to brush up on the requirements and see how your properties stand to benefit.

Read Story