TABLE OF CONTENTS

It’s the 15th annual Park(ing) Day, a day to celebrate creative reuses of parking spaces. Parkade founder Evan Goldin sat down with one of the parklet movement and Park(ing) Day’s founders, John Bela, to look back on the movements’ origins and get his thoughts on the exploding popularity of streeteries during COVID-19.

Evan: Tell me about your history and current relationship with the parklet movement.

John: So, I wear a couple hats these days.

One is as the founder of Rebar in the originators of Park(ing) Day, which was a great active urbanism project that really evolved into a formalized parklet program, which really the city of San Francisco led. We did the activism project, guerilla art project. And it did evolve into a public participatory art project around the world, which we were quite pleased by.

And then in my role as a partner and director at Gehl, I've been really fascinated by this change in the mindset of a lot of our clients, a lot of our municipalities, in terms of the urgency around really thinking about how we use our urban space in our right of way in particular, much differently. So, by way of an example, we won an RFP, won the project in the City of Mountain View to do a yearlong feasibility study of pedestrianizing one block of Castro Street, which you probably know well.

Evan: Oh yeah, I grew up in Palo Alto, right next door.

John: So, it was going to be a year-long study. They anticipated lots of difficult conversations with business and concerns about removing the limited on-street parking that's there. You know, COVID comes along and now — not coming from planning or from the transportation department — but from the economic development department, there's urgency.

They're saying we have to open up our streets to be able to support local businesses to reopen safely. And so all of a sudden, it turns into a four-block summer-long pilot and complete closure of Castro Street, 100 to 400 blocks.

We had to pivot quite quickly from a year-long study into helping them rapidly transform those four blocks to the place where people could use the space safely. But all of the tools that I have been developing and actually haven't been using so much lately that I developed as a Rebar tactician are completely coming back into play for that scale of project.

So really rapidly, quickly, inexpensively figuring out how to creatively transform urban space.

Evan: How did this all begin?

The origins of the parklet project was that we encountered the work of Gordon Matta-Clark, an artist in New York who had a project called Odd Lots where he acquired all these fragments of real estate created as the result of surveying errors. And he proposed all these interventions on these lots but none of them were ever realized.

He died quite young as the artist. But the idea that there are these unscripted spaces in urban areas that weren't overly programmed or commercialized for one particular use or another was very inspiring for us as artists and urbanists wanting to transform how we think about urban space.

We didn't actually find vacant lots until much later. But we came across parking spaces and thought, wow, here's, you know, extraordinarily valuable urban real estate that's subsidized to support storage of private vehicles. And it just brought to light the value system that supported storing private vehicles versus some kind of other use.

We researched the code in San Francisco and determined that it was not illegal to do something other than store a car in a parking space. We actually thought about a bunch of ideas: office space, performance space, coworking, fitness, art exhibition. And we ended up landing on the park concept because in that particular area of downtown, near First and Mission, it was underserved by open space.

And so we thought, cool, let's try to fulfill an unmet need by thinking about this space quite differently.

Evan: What did you think about the fact that these spaces are popping up all the places now, in the form of streeteries?

John: The unmet need today is outdoor work. The unmet need today is outdoor dining.

So it's no surprise to me that there's been a creative response in terms of transforming and rethinking how we value our precious kind of urban real estate and our rights of way. What I'm hoping is that this stimulates the longer, tougher conversations about how we use our streets. And one of the things we've been doing at Gehl is that we've been working with Greenfield Labs, which is Ford's urban/mobility experimentation and research division to create something called the National Street Service.

As cities have this growing conversation around the role of autonomous vehicles and the role of our streets, we felt like the conversation was being shaped or guided more by sort of technological innovation vs. the value set. So we wanted to sort of reframe and level-set with partners in communities about what are the streets that you envision for your community? What are the values you have for your streets and rights of way? And how can those sets of values be as much drivers of conversation as technological evolution so that actually the technology, technological evolution supports the values that we have as citizens about how we use urban space, how we use our streets.

I think in the early days of the parking project and then actually as we started to work with the city of San Francisco and formalize it to do some of the first parklets, I think we always thought that parklets were going to be a gateway or a step toward like a sidewalk widening like they've done on Valencia.

It would always be sort of an interim step toward something else. I am as surprised and pleased as anyone that they've become their own urban space typology.

Evan: Yeah, they really have.

John: They really have. And I think what's different about parklets than a city-led, more top-down, more strategic sidewalk expansion is that these are more user generated.

They reflect the kind of culture and content of that individual neighborhood or that proprietor or that gallery or in many cases, of course, that food-and-beverage business. They reflect the personality of that sponsor or patron. And therefore, they really add this very rich nuance to urban space, which is much different than a more strategic approach to generating more urban space. So that's where I think the enduring value is that — they're both about changing the way we think about urban real estate in our streets and parking spaces, but also they become a kind of an instrument for individual expression in the public space.

Evan: Exactly! It’s funny and fascinating to see the personality of the business come across in what they designed. For example the Front Porch's parklet is very much designed to look like a front porch. And there's other ones that are super spartan, like the burrito shop throwing up some cones and chairs and creating a place for people to sit.

Businesses have always had the ability to control their interior, but often they don't get the ability to design the exterior or streetscape of their space. And this gives them this really interesting opportunity to do that, and do it really cheaply.

Notably, almost all of these new parklets that we're seeing in this current parklet explosion are temporary and they're being done very quickly and cheaply. These are not being done out of, you know, rebar and concrete — they're largely being done out of wood or just whatever items the business has one hand, be wood or it velvet rope. Do you that's the right way to be doing that in this moment, and where do you think that leaves us in the next few months months as the weather changes?

John: One of the things that we really pushed for as Rebar — while working with the city — is that parklets must be public space.

It's not a privatization of the commons for commercial use only. That's a cafe-table-and-chair permit. That's totally fine. But it's a very different thing.

I think the spirit of Park(ing) Day and the spirit of parklets is that it's also an act of urban generosity. And I think what's different about the interior of a restaurant, as you were describing to what happens outside, is that you're interacting with this uncertainty about being in public space, which has its own very unique set of circumstances and conditions, particularly in San Francisco.

It's a really crucial part of how a parklet should function. They’re serving the needs of that individual restaurant or gallery or whatever it is. But they're also making an offering to the public in terms of generosity for a place to sit or some kind of entertainment or some kind of comfort in public or some offering that contributes to the kind of diversity of our public space.

What I'm slightly concerned about with this new wave is that they're all basically, you know, patio seating for private commerce.

I don't know if the signal, you know, to a member of the public is that, oh, I can sit here because it's a parklet, which I've now become familiar with in San Francisco as part of the public realm and part of public space. The design cues are different today.

But also that I know the need is different. I completely support it.

There's this short-term urgency around allowing our restaurants and food and beverage industry to reopen and do it safely. This is one of the major drivers for the project in Mountain View. And there's a lot of debate around open streets and safe streets and whether the equity focus is in terms of who these changed streets are serving.

But I think what hasn't come up in the conversation as much has been the fact that a quarter of the jobs in the US are people who work in retail and service industry. So many of those people are out of work. And so to me, there's actually quite a strong equity lens around how we utilize and how we respond to this particular set of circumstances and how we utilize space regarding who the kind of target audience is.

And yes, it's us as patrons, but it's also very much enabling a lot of these small businesses to get back to work and rehire staff. That's a real critical component of it. So I'm sort of willing to overlook my philosophy that parklets should be always public and always make some kind of generous public offering in the spirit of there being a real urgency around supporting our small local businesses.

Regarding their temporal nature: Some cities in response to COVID have been trying to fast track their parklet programs. But the trick there is, is that even a parklet as sort of light and cheap as they can be, they still cost between $5,000 and $25,000 to sort of do a decently resilient parklet.

A lot of businesses are struggling to get their doors open and don't necessarily have that cash on the one hand, and they probably want to spend it on staff or some other kind of resources. So, I actually think that what San Francisco has done is say, cool, look, we're going to open up the use of the parking lane. We're not going to set a high bar in terms of design standards now because we know there's a real sense of urgency.

On the one hand, I think that's a good thing. On the other hand, what I'm seeing — not so much in San Francisco, but in other cities that are doing this — is that they're allowing the cafe tables to spill out onto the sidewalk. And then a lot of these cities are building out these temporary parklets or pedestrian walkways in the street. And to me, that seems like not quite getting the hierarchy in terms of prioritizing the pedestrian.

To me, pedestrians should always have a clear, safe, legible right of way just for accessibility purposes. For mobility impaired folks, to ask them to step off onto the curb or even onto adapt to sort of move out of the way, seems to me a disservice that I'm not so supportive of in terms of this recent trend of parklet creation.

And I think your question about how this works in the winter, I was just thinking about. Take Atlanta or New York — surely these businesses are able to reopen now with some of the outdoor dining, but how do they handle in the winter how they handle the rain or extreme heat weather? So I think there's going to need to be some greater level of investment in these types of spaces. Maybe that's where your city or municipality kind of comes in to help support grants for small businesses to actually do some of its sturdier in those spaces.

Evan: What have you learned about what works and what doesn't in creating a parklet? Kind of from a design perspective?

John: One thing that people often don't get right in parklets is that there are just some very basic considerations about drainage against the curb. The curb performs a pretty important function of directing stormwater. Not that we're gonna have any water in California for the next three or four months, but, you know, in other areas, it's really easy to overlook even with, like a temporary platform.

The second one is that creating a level platform is pretty important. People seem to be able to solve that part pretty well.

Another big consideration is having a variety of seating types and the signal that that sends to the patrons. Early on in the parklet program, cities decided to encourage restauranteurs to choose a different set of furniture than you're using in your indoor space vs your outdoor patio. So there's a kind of design cue that this is public space — versus this is pay-to-sit-down seating.

Given the sort of urgency of the current crisis, I don't think that's a super relevant factor. If you have chairs, just put them out and use them. For the longer-term thinking, I think some variety of seating type is important.

I think some of the most creative parklets are ones that actually do something with the "air rights," let's say, above the parking space. One of my favorite recent ones is the parklet in front of Dandelion Chocolate, which has beautiful wood bench seating and a variety seating types, a few tables, and then it has this cool overhead canopy. A little bit like a slight bit of enclosure.

Similarly, the Four Barrel parklet was one of the first ones I saw to really take advantage of that kind of space up above to recline vines for trellises or shade. I think there's a lot of ways to creatively use that space that hasn't been done so much.

The other important factor for me is the degree of kind of porosity to the sidewalk. If you have a bunch of clutter or seating or planting, whatever it is on the sidewalk side of your parklet, it's not going to be easy for people to get in and out. And I think that it limits their utility, particularly in COVID times, particularly when part of their role is about making a sidewalk a bit more generous if you have to pass somebody. And then on the street-facing side, I kind of dislike a parklets that just create this wall around them against the street.

And I know there's one attitude about that, which is that it's about pedestrian safety and protection from moving vehicles. But there are very, very few cases where parklet has been collided into by a vehicle. Actually, one of the only ones I know of is on Sunset Boulevard where we built three parklets and actually one of them was hit by a car that skidded out across an intersection and hit the parklet.

But I feel like the parklets that have sort of an opaque wall around them are not a good design solution for a number of reasons. First of all, you want to be able to see a little bit what's going on, I think, in the parklet, otherwise it feels a bit obtuse. And also there's a public safety issue there where someone could sort of hide behind that wall or something. So I think having some of that transparency is kind of good for that reason. So those are all things I think about when making parklets.

And then the final thing is that there's been an incredible expression of creativity in Park(ing) Day and parklets around the world. And I see every opportunity to push it further. Actually, the latest iteration of this was a project I did in 2013. We created something called the Park Cycle Swarm, which was a mobile, pedal-powered public open space. They were literally bicycles that had astroturf, and we built five of them. You could stack them together to create a much larger open space.

That was one of my favorites.

So I'm always interested in the kind of design innovation that is coming of this program, but also this idea about serving humble, everyday life. I mean, parklet can be a beautiful design object, but it falls short unless it's actually accommodating the sort of basic human needs for comfortable seating, for shade, for adequate distance. All those things are crucial. I think that's true of any kind of public-space design project. But it really shows up in a parklet because it's such a small space that you're not kind of getting those marks in terms of everyday human comfort.

Evan: Certainly here in San Francisco, I've seen a ton of these 6-foot tall opaque fencing-style parklets.

John: It's a result of them really serving this kind of short-term, immediate need for space, which again, isn't totally aligned with the kind of fundamental values of what a parklet is. And I think they'll find that actually having this sort of opaque enclosure is going to be a disservice to them over time. Even if you're passing by car, bike or whatever, if you can't see that people they're enjoying the outdoor dining I think it's not taking advantage of those patrons actually being there and showing "Hey, we're open!"

And there's the risk of, you know, people camping out or utilizing that space at night and not being able to see in it or through it. So I think there's a lot of challenges with that. And I assume we'll evolve away from that kind of design.

Evan: What did you learn in creating the initial movement that you think can be put to use today?

John: There's three main themes which the Park(ing) Day and parklet program embodies for me, which continue to be quite relevant in our work in cities and just our work working with public space in general.

I think the first is the idea of flexible urbanism.

One of the great things about streets is that they're adaptable. Streets have been legible throughout the centuries and have retained their fairly similar character over the years, in part because it's a very basic structure. But it's also very adaptable.

The idea of temporarily transforming the parking lane, or even streets, is a great example of thinking creatively about how we use urban space and that maybe it doesn't have to be a full-time, permanent change, but actually can create the ability to be able to respond to changing needs over time.

So flexible urbanism is one thing. The other theme I've been thinking about a lot lately is what I like to call "iterative placemaking."

People have a lot of different terms for this — "lighter, cheaper" or "measure, test, refine" is how Gehl thinks about it. I think about it as iterative placemaking. It’s testing an idea, learning from that idea what's working and what's not working, and then revising your thinking, revising the design to accommodate what you've learned. The best-case scenario for what will happen with these current generation of commercially focused parklets is they'll probably learn some things which really worked and learn others things that don't. But hopefully they'll be able to have that second round of reinvestment, so that things can evolve.

I think that's true of so many of our urban spaces and an approach that would be so useful for so many different things in our city, whether it's how we handle housing for homeless to how we think about urban mobility. I think this idea of testing an idea, learning from it and adapting over time is really key. And then I think the third one is the theme of user-generated urbanism.

This really came up with the Mountain View pilot, actually. We did this design for the four blocks. And, you know, we anticipated people would use a particular way. And of course, as things open up and you really connect with the users of that space, they shape it and use it in so many ways that you could never have predicted.

I'm really interested in this tension between the strategic frame and then who populates that frame with content. So whether it's like user-generated content on the Web or user-generated content in our cities, there's some kind of strategic frame and there's some kind of response by the user or the public, which I think is always so interesting, that kind of interface.

Those three themes that I think emerged with Park(ing) Day and emerged as part of a broader global movement of tactical urbanism and continue, I think, to be important in shaping our cities, in particular how we're responding to this sort of short-term shock to the system of COVID. It may be that we don't know how short this is going to be. But I also think that there's this mindset shift that is really going to help us as we try to adapt to the larger challenges which are going to face our cities, which is responding to climate crises. Many other things that are going to continue to put pressure on us, our communities and how we think about and use urban space.

Evan: In most places, it was either unclear or illegal to create a parklet just three months ago. Now, all of a sudden, there's emergency ordinances all over the country, and a lot of those will expire. What recommendations do you have for a business or neighborhood that's been inspired to rethink their space more permanently?

John: Fortunately, the city of San Francisco has done a great job of crafting that early pavement-to-parks program.

It's now called Ground Play, which is a really great portal to anything you want to do in terms of shaping urban space, whether it's a block party or a parklet application.

And they've spent a lot of time working on both the kind of backend — in terms of coordination with city agencies — but also the user interface regarding how you as a member, the public can understand how to navigate through that process. They've really streamlined that process to the extent that you can in, as far as the kind of complex bureaucracy San Francisco has.

Because San Francisco has done that work, Seattle has done that work, L.A. has done that work, you don't need to reinvent the wheel. And so, you know, Nashville, after talking about it for and doing Park(ing) Day for 10 years, has now just recently introduced a parking ordinance. And I'm sure they borrowed that ordinance language from one of the other cities. So this is a great thing.

A lot of the groundwork has been laid in terms of inter-departmental coordination, in terms of permit fees and terms of all the stuff. And then also in terms of the kind of public-facing interface regarding how easy it is for someone to be able to navigate the program.

So on the business-owner side, just look to another city, download San Francisco's parklet manual manual, and share it with your council member or share it with the mayor. Tell them that this work has been done around the world and that you're actually now an advocate.

You weren't three months ago and you were concerned about that individual parking space in front of your business. But now you see the value in raising the value proposition for using that space.

So a lot of tools out there.

From the city side I would say, as this grows, I think it's going to be very important to have the focus or the lens of geographic equity. This is something that actually the city of San Francisco understood pretty quickly after the parklet program was launched. Because: "hmm, we're only getting applicants from neighborhoods with more political capital or neighborhoods with more upper-income residents. Why is that?"

Well, I think this is harder for people who aren't as familiar with navigating through government or are intimidated by the fees or there's language barriers. So the City of San Francisco did a great thing, which is to really focus on going to go out to neighborhoods where they've expressed a desire for this, but we're not seeing the program being taken advantage of yet. And actually coax people through the process.

So that's something on the city side and I think is important to know. Let's help our neighborhoods in the Bayview. Let's help our neighborhoods in the Western Addition to take advantage of this new program that the city's rolled out. Then, you know, the Valencia corridor and Polk street corner and so forth.

Evan: My favorite question, of course, is about parking. Eventually, as COVID-19 hopefully recedes, we're likely to see a lot of people start to complain about "OK, now where do I park my car?" Whether it's someone that wants to use a parklet, someone that wants to create a parklet or someone who is planning department or elected official trying to create policies to support them, how do they handle those complaints? Are there any new tactics that you think might have revealed themselves in the past few months as we've seen all these parklets pop up? Or, you know, is it just going to end up being the same debate of "but where will I park?"

John: Well, someone told me about this great new app called Parkade that helps take cars off the street and find them better places to park!

Evan: Hah, of course, of course. And we're excited to play a role there.

John: Beyond that, most cities are at different levels in terms of their evolution in managing parking.

It is so clear that we have to manage it as a resource and carefully manage our parking, either in terms of pricing, as you mentioned you did with your experiment charging for parking at Lyft HQ, but also just really maximizing the utilization of the existing parking we have.

I’m excited to see new architecture in various parts of the world using stacking parking or robotic parking structures. So making better use of the limited urban space we have put, but pricing it appropriately is a key part of the equation. And many cities have 60 or 70-percent vacancy in their residential and city-owned parking garages. So I'm really pleased to hear that you're trying to kind of solve that part of the problem.

And what that does for us overall, if we have read Donald Shoup, we know that parking and pricing it appropriately is going to result in lower demand overall and allow us to achieve a lot of the kind of things that I referred to earlier in terms of better utilization of our urban space. It just makes no sense that, you know, 20 to 30 percent of a particular urban areas, land areas dedicated to storing private vehicles.

We could be doing that so much more efficiently through parking management or innovation in parking structure design. And ultimately, I think generationally, we need to make the investments in transit. That's what's so disturbing about the kind of COVID trend moving away from transit that actually is pushing us in the wrong direction.

We have to be investing heavily, even heavier in, you know, entities like Caltrain to make sure that it's safe to ride and make sure that it's going twice as fast and, you know, make sure that every street in San Francisco has a dedicated transit lane. Wouldn't that be an incredible outcome of this — so that we really use this kind of time to shift the mindset in terms of how we prioritize and what forms of mobility we prioritize in cities?

Evan: My last question, of course, is that I have to ask you to tell me which parklet is your favorite in the world.

John: think in terms of the most recent memories, enjoying sitting on a parklet — it's the one in front of Dandelion.

Yes, I'm there myself with my son. And it's just kind of a comfortable space, with the right amount of enclosure. It has really nice materials, and just wonderful place to enjoy street life. You know, at least a month ago on Valencia, it was like the best spot. It really felt very inviting. And it really signaled that this is a public space. So that's one of my favorites.

So many I mean, they're all over the world now. And some of my favorites are in Argentina, where they've done really creative use of that above-grade space, with these sort of illuminated volumes that define the space above the parklet pretty well.

.jpg)

As parking management becomes increasingly digital, security becomes critical — and we’re excited to share that we've achieved a major security milestone.

Read Story

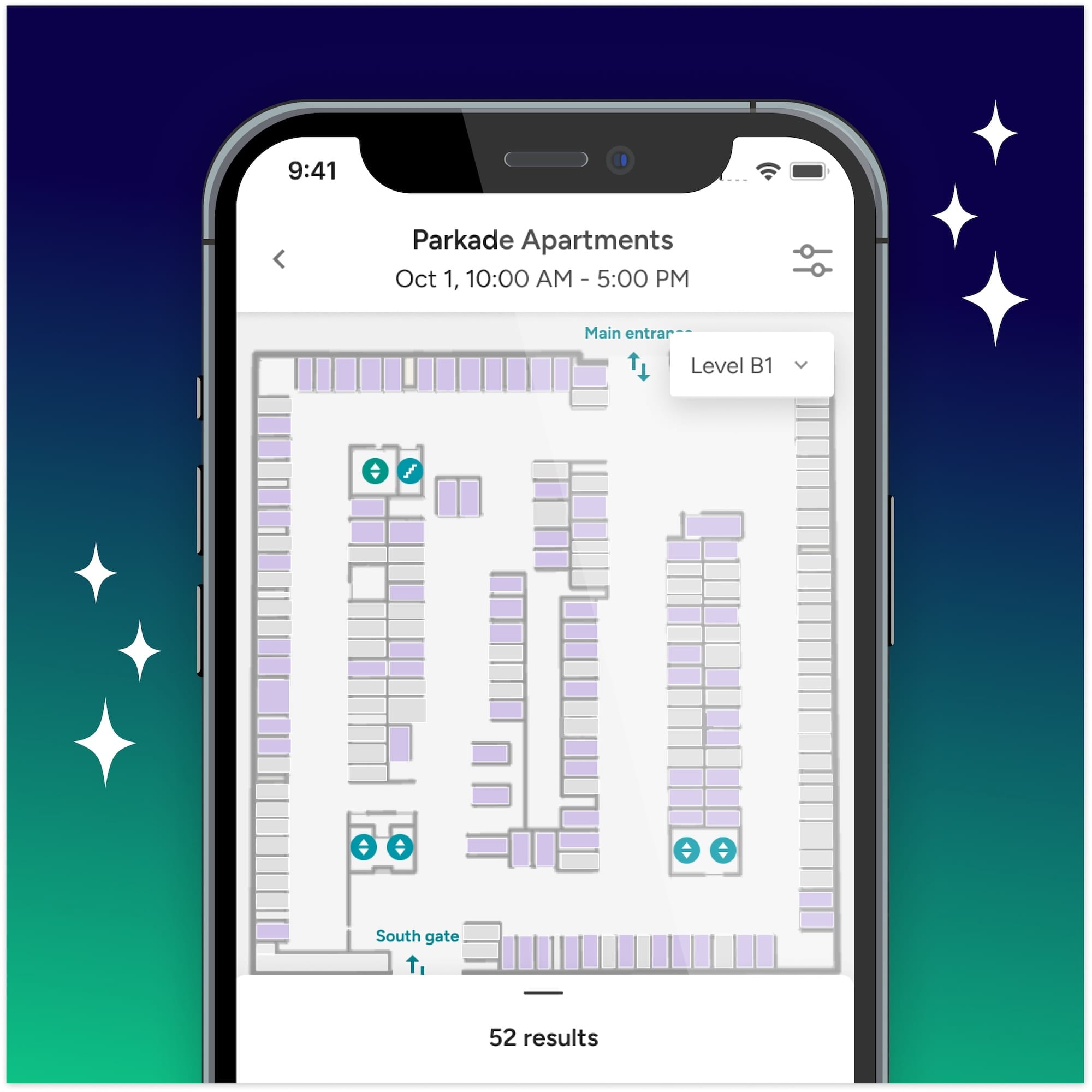

We’re thrilled to announce one of our most significant leaps forward this year: the launch of dynamic maps across our mobile and web applications.

Read Story

Now that AB 1317 is official, it’s time to brush up on the requirements and see how your properties stand to benefit.

Read Story